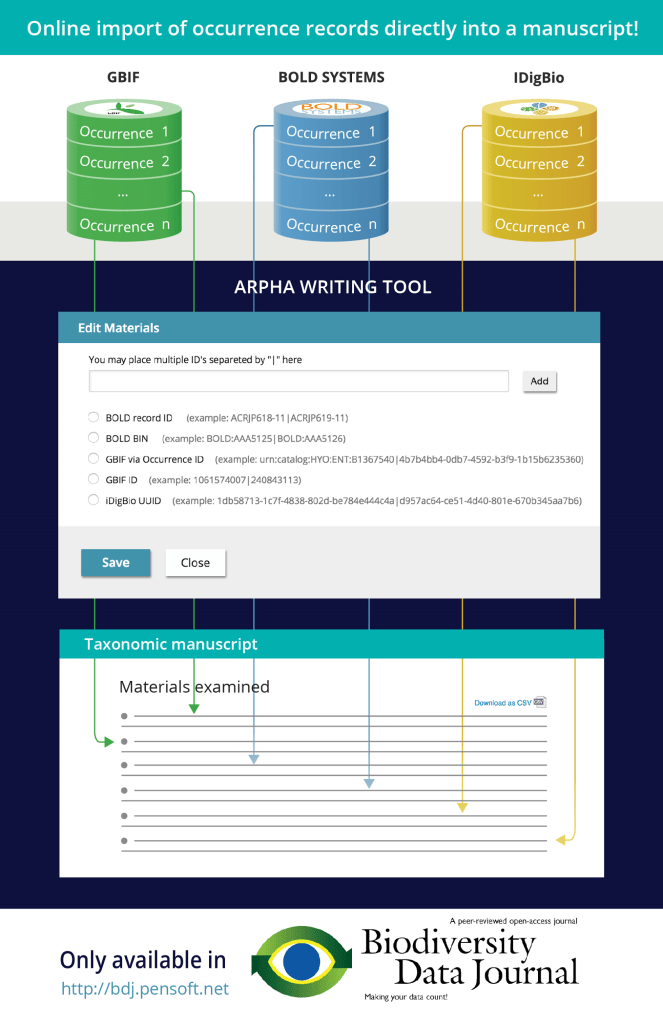

Repositories and data indexing platforms, such as GBIF, BOLD systems, or iDigBio hold documented specimen or occurrence records along with their record ID’s. In order to streamline the authoring process, save taxonomists’ time, and provide a workflow for peer-review and quality checks of raw occurrence data, the ARPHA team has introduced an innovative feature that makes it possible to easily import specimen occurrence records into a taxonomic manuscript (see Fig. 1).

For the remainder of this post we will refer to specimen data as occurrence records, since an occurrence can be both an observation in the wild, or a museum specimen.

Fig. 1: Workflow for directly importing occurrence records into a taxonomic manuscript.

Until now, when users of the ARPHA writing tool wanted to include occurrence records as materials in a manuscript, they would have had to format the occurrences as an Excel sheet that is uploaded to the Biodiversity Data Journal, or enter the data manually. While the “upload from Excel” approach significantly simplifies the process of importing materials, it still requires a transposition step – the data which is stored in a database needs to be reformatted to the specific Excel format. With the introduction of the new import feature, occurrence data that is stored at GBIF, BOLD systems, or iDigBio, can be directly inserted into the manuscript by simply entering a relevant record identifier.

The functionality shows up when one creates a new “Taxon treatment” in a taxonomic manuscript prepared in the ARPHA Writing Tool. The import functions as follows:

- the author locates an occurrence record or records in one of the supported data portals;

- the author notes the ID(s) of the records that ought to be imported into the manuscript (see Fig. 2, 3, and 4 for examples);

- the author enters the ID(s) of the occurrence records in a form that is to be seen in the materials section of the species treatment, selects a particular database from a list, and then simply clicks ‘Add’ to import the occurrence directly into the manuscript.

In the case of BOLD Systems, the author may also select a given Barcode Identification Number (BIN; for a treatment of BIN’s read below), which then pulls all occurrences in the corresponding BIN (see Fig. 5).

Fig. 2: (Left) An occurrence record in iDigBio. The UUID is highlighted; Fig. 3: (Right) An occurrence record in GBIF. The GBIF ID and the Occurrence ID is highlighted. (Click on images to enlarge)

Fig. 4: (Left) An occurrence record in BOLD Systems. The record ID is highlighted.; Fig. 5: (Right) All occurrence records corresponding to a OTU. The BIN is highlighted. (Click on images to enlarge)

We will illustrate this workflow by creating a fictitious treatment of the red moss, Sphagnum capillifolium, in a test manuscript. Let’s assume we have started a taxonomic manuscript in ARPHA and know that the occurrence records belonging to S. capillifolium can be found in iDigBio. What we need to do is to locate the ID of the occurrence record in the iDigBio webpage. In the case of iDigBio, the ARPHA system supports import via a Universally Unique Identifier (UUID). We have already created a treatment for S. capillifolium and clicked on the pencil to edit materials (Fig. 6). When we scroll all the way down in the pop-up window, we see the form which is displayed in the middle of Fig. 1.

Fig. 6: Edit materials.

From here, the following actions are possible:

- insert (an) occurrence record(s) from iDigBio by specifying their UUID’s (universally unique identifier) (Fig.2);

- insert (an) occurrence record(s) from GBIF by entering their GBIF ID’s (Fig.3);

- insert (an) occurrence record(s) from GBIF by entering their occurrence ID’s (note that unfortunately not all GBIF records have an occurrence ID, which is to be understood as some sort of universal identifier) (Fig. 3);

- insert (an) occurrence record(s) from BOLD by entering their record ID’s (Fig. 4);

- insert a set of occurrence records from BOLD belonging to a BIN (barcode index number) (Fig. 5).

In this example, select the fifth option (iDigBio) and type or paste the UUID b9ff7774-4a5d-47af-a2ea-bdf3ecc78885 and click Add. This will pull the occurrence record for S. capillifolium from iDigBio and insert it as a material in the current paper (Fig. 6). The same workflow applies also to the aforementioned GBIF and BOLD portals.

Fig. 7: Materials after they have been imported.

This workflow can be used for a number of purposes but one of its most exciting future applications is the rapid re-description of Linnaean species, or new morphological descriptions of species together with DNA barcode sequences (a barcode is a taxon-specific highly conserved gene that provides enough inter-species variation for statistical classification to take place) using the Barcode Identification Numbers (BIN’s) underlying an Operational Taxonomic Units (OTU). If a taxonomist is convinced that a species hypothesis corresponding to OTU defined algorithmically at BOLD systems clearly presents a new species, then he/she can import all specimen records associated with that OTU via inserting that OTU’s BIN ID in the respective fields.

Having imported the specimen occurrence records, the author needs to define one specimen as holotype of the news species, other as paratypes, and so on. The author can also edit the records in the ARPHA tool, delete some, or add new ones, etc.

Not having to retype or copy/paste species occurrence records, the authors save a lot of efforts. Moreover, they automatically import them in a structured Darwin Core format, which can easily be downloaded from the article text into structured data by anyone who needs the data for reuse.

Another important aspect of the workflow is that it will serve as a platform for peer-review, publication and curation of raw data, that is of unpublished individual data records coming from collections or observations stored at GBIF, BOLD and iDigBio. Taxonomists are used to publish only records of specimens they or their co-authors have personally studied. In a sense, the workflow will serve as a “cleaning filter” for portions of data that are passed through the publishing process. Thereafter, the published records can be used to curate raw data at collections, e.g. put correct identifications, assign newly described species names to specimens belonging to the respective BIN and so on.

Additional Information:

The work has been partially supported by the EC-FP7 EU BON project (ENV 308454, Building the European Biodiversity Observation Network) and the ITN Horizon 2020 project BIG4 (Biosystematics, informatics and genomics of the big 4 insect groups: training tomorrow’s researchers and entrepreneurs), under Marie Sklodovska-Curie grant agreement No. 542241.