The demand for rare raw materials, such as cobalt, is fuelling the exploration of the deep-sea floor for mining. Commercial deep-sea mining is currently prohibited in areas beyond national jurisdiction, but companies are permitted exploratory operations in certain areas to assess their mineral wealth and measure environmental baselines. The Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) is an area of the Pacific deep-sea floor spanning up to 6 million km2, found roughly between Hawaii and Mexico. Currently, it has 17 contracts for mineral exploration covering 1.2 million km2. However, despite relatively extensive mineral exploration beginning in the 1960’s, baseline biodiversity knowledge of the region is still severely lacking. Even the most basic scientific question: “What lives there?” has not been fully answered yet.

In a new paper researchers report on the marine life of the CCZ, focusing on annelid worms. Annelids represent one of the largest group of macroinvertebrates living within the mud covering the sea floor of CCZ, both in terms of number of individuals and the number of species. Data from recent oceanographic cruises enabled researchers from the University of Gothenburg, Sweden and the Natural History Museum London to discover more than 300 species of annelids from around 5000 records. The annelid species, many considered to be new to science, were discovered through employment of traditional morphological approaches and modern molecular techniques. The current study focuses on 129 such species across 22 annelid families. Previously, the authors of this study formalized 18 new species, while altogether reporting on 60 CCZ species, including most recently 6 species in family Lumbrineridae. The lead author Helena Wiklund from University of Gothenburg comments: ‘Taxonomy is the most important knowledge gap we have when studying these unique habitats and the potential impact of mining operations. We need to know what lives there to inform the protection of these ecosystems.”

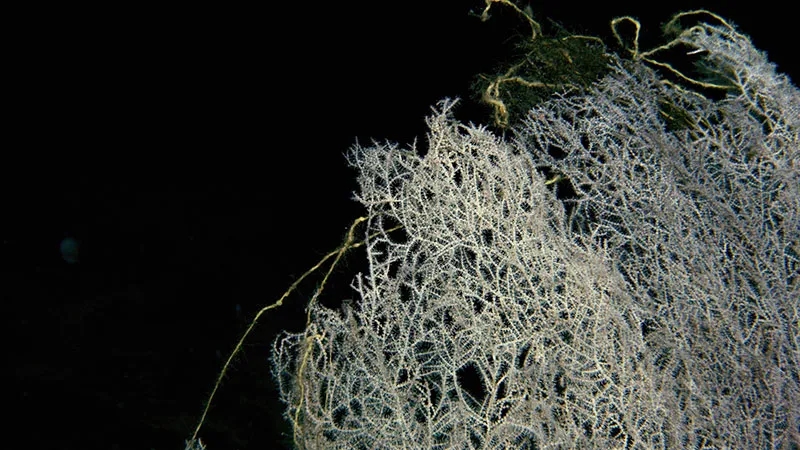

To further understand the CCZ, scientists sail the Pacific Ocean on research expeditions that employ sampling techniques ranging from the technical, like remote-controlled vehicles that traverse the ocean floor, to the simple, like a sturdy box corer collecting sediment at the bottom.

“Sadly, the soft-bodied annelids are often damaged during the collection and sediment sieving onboard” says annelid taxonomist Lenka Neal from the Natural History Museum London. As a result, the traditional morphological approach is often of limited use when working with the deep-sea specimens, with taxonomists increasingly employing DNA techniques as well.

Over the last decade, scientists have generated a large amount of annelid data. Such data are only of use when made available through publication to the wider scientific community and other stakeholders. “A priority is to make the data are FAIR, or Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable so it can be redeployed easily, if you’ll excuse the pun, for future analysis” says co-author Muriel Rabone. “The same applies to samples, where accessibility of the specimen vouchers and molecular samples allows for reproducibility and continuation of the work. This is one step of the process. And ultimately, having more robust knowledge can lead to more robust evidence-based environmental policy”.

“More often than not, ecological papers describing biodiversity do not include a list of all the species and specimens used to make the broader ecological inferences, and even more rarely make the specimens and all associated metadata available in a FAIR way. In this study, we have made a significant and time-consuming attempt to do this, in a region of the global oceans where critical policy decisions are being made that could impact the way humanity obtains its resources and manages its environment in a sustainable way,” the researchers write in their paper, which was published in the open-access Biodiversity Data Journal.

The team behind the research hope that this still partial checklist of CCZ annelids, many in too poor state of preservation to be immediately described, is a key step forward towards creating future field guides for the area’s wildlife. Given that mining operations in the area could be imminent with the International Seabed Authority considering applications this year, the use of biological data for environmental management has become more important than ever.

This research was supported by funding from UK Seabed Resources Ltd.

Research article:

Wiklund H, Rabone M, Glover AG, Bribiesca-Contreras G, Drennan R, Stewart ECD, Boolukos CM, King LD, Sherlock E, Smith CR, Dahlgren TG, Neal L (2023) Checklist of newly-vouchered annelid taxa from the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, central Pacific Ocean, based on morphology and genetic delimitation. Biodiversity Data Journal 11: e86921. https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.11.e86921

Follow Biodiversity Data Journal on social media: