Early detection of pest infestation is an important first step in the adoption of control measures that can be tailored to specific local conditions. Remote sensing technology can be a helpful tool, allowing the quick scanning of large areas, but it’s not universally applicable as sometimes items can be hard to detect. Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), or drones, on the other hand, can help by getting closer to individual trees and detecting smaller atypical signals.

The pine processionary moth is an insect infesting trees in gardens and parks, threatening public health because of the hairs released by its larvae, which can cause a stinging or itching sensation. The pest is rapidly growing in numbers and conquering new territories, which makes it a species of concern.

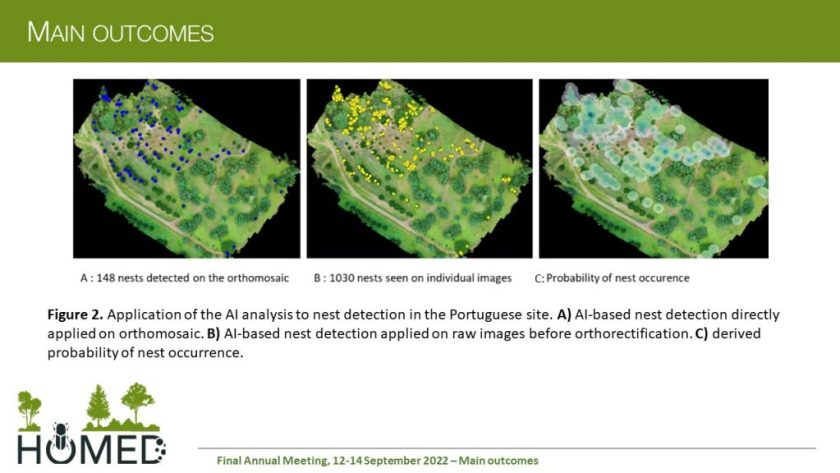

In a new study, researchers tested different deep learning methods to detect the nests made by pine processionary moth larvae on pine and cedar trees. Drones flying over the trees took images, which were then analysed with the help of artificial intelligence (AI) to identify and localise the nests.

The use of AI on drone images proved effective to detect pine processing moth nests on trees of different species and sizes, even under variable densities. The method can be successfully used in both forest and urban settings to help detect moth nests. That way, tree health managers can be informed about where the nests are and take appropriate measures to contain the damage and the public health risks.

“The study proved the advantage of using UAVs to document the presence of at least one nest per tree,” the researchers write in their study, which was published in a special issue of the journal NeoBiota dedicated to forest pests in Europe. “It therefore represents a substantial step forward in the integration of the UAV survey with ground observations in the monitoring of the colonies of an important forest defoliating insect in the Mediterranean area.”

Furthermore, they suggest that the method can be extended to other pests.

“This technique can pave new avenues in the surveillance and management of emerging and non-native pests of trees, where early detection and early action should go together to achieve a satisfactory level of protection,” the study authors write in conclusion.

Research article:

Garcia A, Samalens J-C, Grillet A, Soares P, Branco M, van Halder I, Jactel H, Battisti A (2023) Testing early detection of pine processionary moth Thaumetopoea pityocampa nests using UAV-based methods. In: Jactel H, Orazio C, Robinet C, Douma JC, Santini A, Battisti A, Branco M, Seehausen L, Kenis M (Eds) Conceptual and technical innovations to better manage invasions of alien pests and pathogens in forests. NeoBiota 84: 267-279. https://doi.org/10.3897/neobiota.84.95692